Return to Sport after ACL Injury

Let’s all admit it, the sport participation landscape has changed drastically over the past 30 years.

When I was growing up, we played 4-5 different sports throughout the year, had actual gym teachers that taught us to run, jump and land and played outside. Times have since changed; today’s sporting youth are more skilled, more specialized, and unfortunately, more injured. As strength and conditioning coaches, team trainers and physical therapists, we must adjust to this less-than-ideal development model.

Some stats…

The incidence of ACL tears in pediatric patients increased over the last 20 years.1 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the increase in ACL injuries among 14–18-year-olds is 147.8%. The data suggests, females were at higher risk, except in the 17- to 18-year -old group. And peak incidence is noted during high school years.2

While ACL tears are one of the most common knee injuries, repeat ACL injury is also tragically happening for 25-33 percent of young athletes playing sports, according to recent data (2023) presented at the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine’s AGM. It makes one wonder what the rehabilitation process looked like and perhaps what their physical status was like even before the very first knee trauma.

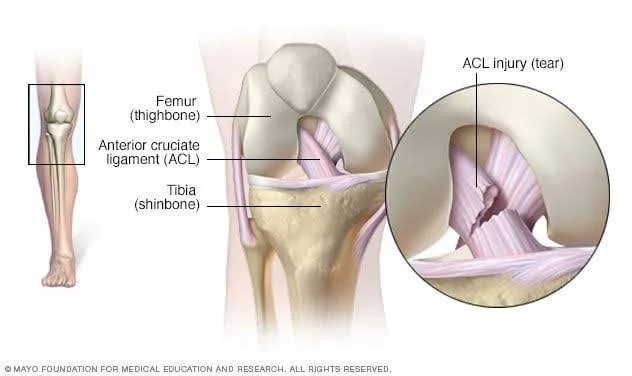

An ACL ligament rupture is considered a traumatic knee injury that often (but not always) requires surgery to return to play. The ACL ligament is one of the strong bands of connective tissue that help connect your thigh bone (femur) to your shinbone (tibia).

How do ACL injuries happen? (Common causes of ACL injury)

ACL injuries often happen during sports and physical activities that involve knee-dominant movements such as:

- Suddenly decelerating and changing direction (cutting)

- Landing from a jump (especially one-foot landings)

- Pivoting on the spot with your foot firmly planted

- Receiving a direct blow to the knee or having a collision, such as a football or soccer tackle. *This is a contact ACL injury.

But let’s back up a minute here. Sure, those are the potential biomechanical mechanisms for injury, but what is commonly known about those who are more susceptible to injury? Well, from my experience a theme has emerged:

- Musculoskeletal immaturity – meaning they do not have the level of strength and control to handle the stressors of the sport (but I bet they can hit a 3-pointer)

- Lack of understanding of ‘load’ – Load is the amount of physical exercise an athlete is getting per week. There might be a mismatch between the amount of load and what the athlete tolerate or what is reasonable for their age and stage of development.

- Lack of ‘real’ strength training – Can the athlete nail 20 push-ups with strict form and do 5 pull-ups? Can they perform a controlled SL squat and hop on one foot without their arch collapsing or their hips dropping? These are just a few tasks that (in my opinion) all healthy 13-year-olds should be able to do.

- Poor movement competency – Movement is specific to sport, but all movements should be graded against a technical model. Movements outside of that model need to be corrected and improved.

Here is an example of a 13 year old (yes, he’s my kid) performing a lateral split leap with load outside of his center of mass to challenge his posture.

In my quest to solve the ACL riddle, I focus on the non-contact injuries. These are possibly easier to risk mitigate. Notice I did not say ‘prevent ACL injury.’ That is a bold endeavor and because there are so many factors that could lead to increased injury risk; it is tough to make this type of promise. However, I will share, with you some of the reasons why I personally think we need to do better.

Here's a short video where I rant a little bit about where things are at in the rehab literature:

The Million Dollar Question I get is: What is the recovery time for ACL Rehab?

First, I will state that the only aspect of ACL rehab that follows a timeline is the initial tissue healing process – tissue does require time to repair itself and that I can and do appreciate. The surgeon will give clear guidelines in this area, especially with respect to the type of graft they chose. Beyond tissue and graft healing, the timeline of recovery will depend on the following:

- How quickly an athlete restores their range of motion at the joint

- How quickly an athlete can recover from swelling (it is normal for the knee to swell from the rehab exercise but should not persist)

- The training age of the athlete prior to the injury – this means if they do not have a foundation of movement competency and muscular strength, the rehab process will become a physical preparation process.

- How detrained an athlete becomes waiting for surgery – oftentimes athletes do not know there is a great deal they can still do to maintain and retain their fitness qualities.

Although much of the literature is based on timelines, this approach is not grounded in reality. Sure, the new graft may have healed but there could still be massive deficits in:

- the ability of the athlete to control their body in space,

- their overall levels of tensile strength,

- their repeat power ability and more.

Return to sport testing batteries must be incredibly comprehensive from the physical to the psychological and include the technical and tactical. That’s a blog for another day…

In 2009 a study reported 22% of NBA players failed to return. Of the 78% who returned, 44% were not performing at the same level based on match statistics. The statistics were the same for WNBA players. 3

In 2010, a study in the NFL, under 80% of players return to sport. But took over 12 months. And these players had performance deficits based on match data analysis. 4

Tip for Returning to Sport after an ACL repair – It takes a Village

My personal mission for tackling this ACL injury epidemic is to educate and empower parents and athletes for long term success. It is important that the athlete undergoing ACLR rehabilitation and looking to return to sport after acl reconstruction has a team of practitioners around them. And that team must be on the same page and be in constant communication. In a perfect world (why not aim for that), the athlete has both a physical therapist or athletic therapist AND a strength and conditioning coach. The two roles have different skills sets.

Here's an example of how a practitioner support team can be integrated:

- The physical therapist can handle the early-stage rehab using modalities and manual techniques to restore range of motion and reduce edema. Electrical stimulation can also assist with quadriceps activation, which is critical early on.

- The strength and conditioning coach can also be involved during early stage rehab take them through a safe strength training routine that targets the areas of the body not affected by the surgery and when the time is right (medical clearance), get the athlete in the pool for movement retraining and conditioning. This is critical and as far as I am concerned, a 15-year-old should get the same service as the Pro athlete and not be passed like a baton at the 6-month mark.

- The sport coach can invite the athlete to practice and games and continue to include the athlete as a key part of the program or team. Maybe they can also spend more time watching film and scouting their opponents or learning a defensive scheme to stay sharp and involved. There are even likely sport skills that can be practiced while recovering if they are modified. Coaches can provide these ideas.

The bottom line about Return to Sport after ACLR

The most successful cases I have worked on after ACL reconstruction surgery is where the athlete feels supported and included and the program is individualized. Timelines must be abandoned, and the programming must be agile. There will be good days and days where the hill seems even steeper. ACL rehabilitation is a non-linear process.

We also cannot wait to week 16 to begin ‘strength & conditioning’ as too much time is lost by then. And one practitioner cannot likely do all aspects of rehab so right from the start, everyone must be involved.

References

1 Nicholas A. Beck, J. Todd R. Lawrence, James D. Nordin, Terese A. DeFor, Marc Tompkins; ACL Tears in School-Aged Children and Adolescents Over 20 Years. Pediatrics March 2017; 139 (3): e20161877. 10.1542/peds.2016-1877

2 Nicholas A. Beck, J. Todd R. Lawrence, James D. Nordin, Terese A. DeFor, Marc Tompkins; ACL Tears in School-Aged Children and Adolescents Over 20 Years. Pediatrics March 2017; 139 (3): e20161877. 10.1542/peds.2016-1877

3 Busfield BT, Kharrazi FD, Starkey C, Lombardo SJ, Seegmiller J. Performance outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the National Basketball Association. Arthroscopy. 2009 Aug;25(8):825-30. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.02.021. PMID: 19664500.

4 Mody KS, Fletcher AN, Akoh CC, Parekh SG. Return to Play and Performance After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in National Football League Players. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022 Mar 7;10(3):23259671221079637. doi: 10.1177/23259671221079637. PMID: 35284583; PMCID: PMC8905068.